Early adversity profoundly affects diverse aspects of child development, including brain development, physiological reactivity to stress, and long-term risk for mental illness. Most models of these effects focus on the number rather than character of adverse childhood experiences.

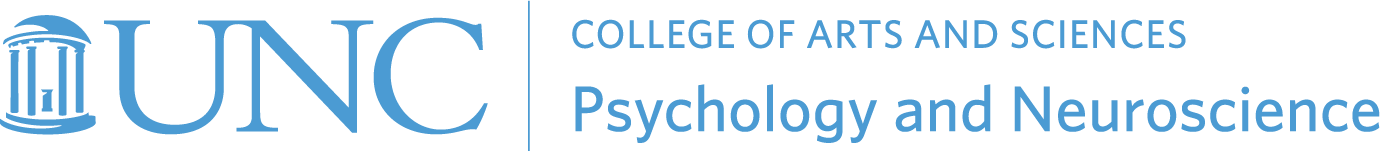

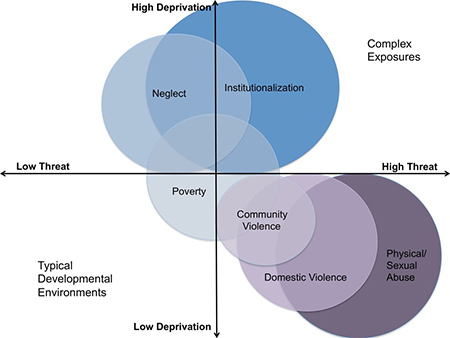

In Dr. Margaret Sheridan’s laboratory, researchers test a novel conceptual model of the impact of adversity on neurobiology and risk for mental health problems focused on the type of exposure. In theory papers, Dr. Sheridan advocates for differentiating between two primary dimensions of experience underlying multiple forms of adversity: deprivation and threat (Sheridan & McLaughlin, 2016; Sheridan & McLaughlin, 2014). Deprivation involves a lack of enriching and species expectant cognitive and social inputs (e.g., neglect). Threat involves actual or perceived danger to the physical integrity of the child (e.g., exposure to violence).

In Dr. Margaret Sheridan’s laboratory, researchers test a novel conceptual model of the impact of adversity on neurobiology and risk for mental health problems focused on the type of exposure. In theory papers, Dr. Sheridan advocates for differentiating between two primary dimensions of experience underlying multiple forms of adversity: deprivation and threat (Sheridan & McLaughlin, 2016; Sheridan & McLaughlin, 2014). Deprivation involves a lack of enriching and species expectant cognitive and social inputs (e.g., neglect). Threat involves actual or perceived danger to the physical integrity of the child (e.g., exposure to violence).

Since Dr. Sheridan first published this theory, she has had the opportunity to test her hypothesis that deprivation and threat increase risk for psychopathology through separable neurobiological pathways. Most recently, Dr. Sheridan examined this hypothesis in two studies measuring executive function at multiple levels: performance on executive function tasks, neural recruitment during executive function, and problems with executive function in daily life.

In Study 1, deprivation (low parental education and child neglect) was associated with greater parent-reported problems with executive function in adolescents (N=169; 13-17 years) after adjustment for levels of threat (community violence and abuse), which were unrelated to executive function. In Study 2, low parental education was associated with poor working memory performance and inefficient neural recruitment in parietal and prefrontal cortex during high working memory load among adolescents (N=51, 13-20 years) after adjusting for abuse, which was unrelated to working memory task performance and neural recruitment during working memory. These findings are in press at Development and Psychopathology. Previous work supporting this disassociation can be found here: (Busso, McLaughlin, & Sheridan, 2016; McLaughlin, Peverill, Gold, Alves, & Sheridan, 2015) and in ongoing work in the Child Imaging Research on Cognition and Life Experiences (CIRCLE) lab at UNC.

In Study 1, deprivation (low parental education and child neglect) was associated with greater parent-reported problems with executive function in adolescents (N=169; 13-17 years) after adjustment for levels of threat (community violence and abuse), which were unrelated to executive function. In Study 2, low parental education was associated with poor working memory performance and inefficient neural recruitment in parietal and prefrontal cortex during high working memory load among adolescents (N=51, 13-20 years) after adjusting for abuse, which was unrelated to working memory task performance and neural recruitment during working memory. These findings are in press at Development and Psychopathology. Previous work supporting this disassociation can be found here: (Busso, McLaughlin, & Sheridan, 2016; McLaughlin, Peverill, Gold, Alves, & Sheridan, 2015) and in ongoing work in the Child Imaging Research on Cognition and Life Experiences (CIRCLE) lab at UNC.

Dr. Sheridan is an Associate Professor in the Clinical Psychology Program within the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience at UNC Chapel Hill. Her lab is focused on using neuroscience to solve real world problems such as better diagnosing ADHD or creating safer, healthier environments for children growing up in poverty. Learn more about the Child Imaging Research on Cognition and Life Experiences Lab.